Growing Together Spring 2025

From Rice Fields to Rivers

The California Rice Commission (CRC) and research partners are finishing a plan to guide rice producers who want to provide juvenile salmon with food-rich, winter-flooded fields within the Yolo and Sutter bypasses. The goal is to fatten up the roughly 2-inch-long fish on zooplankton naturally found in the Sacramento River floodplain so they are larger and have a better chance of survival as they migrate to the sea.

If the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) accepts the plan as a conservation practice standard, rice producers may be eligible for cost-share funding to help implement it.

But Andrew Rypel, a University of California, Davis, fish ecologist leading the California Ricelands Salmon Project research, said the plan is not the lone silver bullet to help recovery of imperiled Chinook salmon runs. Instead, he sees it as part of an overall effort that also includes dam removal and habitat restoration.

“It’s pretty dark times for salmon right now,” he said. “There are a lot of reasons. It’s not just that they can’t get on the floodplains. They’re dealing with major factors like domestication with hatchery fish and pollution. So (the project) is one factor that can help.

“Again, it’s not going to save the day. But if you get enough of these strategies, you can put them together in a portfolio that will help.”

While Rypel said he is confident in the rice field practice, state and federal fishery agencies are concerned about how the practice could interact with federally and state-protected Chinook salmon runs, said CRC Manager of Environmental Affairs Paul Buttner.

“We believe we have enough science already to move forward into an initial implementation phase while they would prefer more studies before we do more widespread implementation,” he said.

GROW WEST STEPS UP

The California Ricelands Salmon Project involves more than six years of collaboration between the CRC and the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, which Rypel heads. The commission received two consecutive three-year NRCS grants beginning in 2018 to help fund the work.

Grow West became involved with the project because of its long-standing relationship with the California Rice Commission.

“It ties back to the community, particularly since rice is so big for the north state, for the customers we serve and for Grow West. It’s neat to see the rice industry making a devoted effort to focus on habitat, and this fits nicely into that.”

Grow West Vice President and COO Lucas Schmidt

As with most NRCS grants, Buttner said these required matching funds. Without additional financial support – such as from Grow West, which has been a donor since 2018 – he said the project wouldn’t have been as successful.

Grow West became involved because of its long-standing relationship with the CRC, said Grow West Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Lucas Schmidt. As part of its continued commitment to the Northern California community – as well as to CRC’s efforts to improve wildlife habitat – the Grow West management team decided to financially support the project from the start.

“It ties back to the community, particularly since rice is so big for the north state and for the customers we serve and for Grow West,” Schmidt said. “It’s neat to see the rice industry making a devoted effort to focus on habitat, and this fits nicely into that.”

Having watched what started out as a pilot project evolve into its current farm-scale status, Schmidt said he remains optimistic the research leads to a program California rice producers can use and support.

In addition to Grow West, current project sponsors include Corteva Agriscience, American Commodity Co. Inc., California Family Foods, California Rice Research Board, California Ricelands Waterbird Foundation, Lundberg Family Farms, Northern California Water Association and the Nigiri Project – Cal Marsh & Farm Ventures. Phase one sponsors included Almond Board of California, Conaway Preservation Group, NovaSource Tessenderlo Group, River Garden Farms, S.D. Bechtel Jr. Foundation–Stephen Bechtel Fund and Valent.

FLOODPLAIN FATTIES

Despite popular beliefs, Rypel said the Sacramento River is not teeming with food for young salmon. Historically, the river topped its banks during winter, inundating adjacent floodplains. The flooded areas were rich in zooplankton, microscopic marine organisms on which the salmon gorged before they migrated to the ocean.

As river levees were built, floodplains shrunk in size. But the Nigiri Project, started in 2011, found winter-flooded rice fields could mimic floodplain fish-rearing habitat. The project was a joint effort among the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, the California Department of Water Resources, the nonprofit California Trout (CalTrout) and private landowners within the Yolo Bypass.

Preliminary studies conducted during the mid-2010s found zooplankton in the winter-flooded rice fields were 53 to 150 times more abundant than samples from the neighboring Sacramento River. At the same time, researchers found hatchery-sourced juvenile fall-run Chinook salmon stocked in the rice fields grew two to five times faster than similar-aged fish in the adjacent Sacramento River.

CRC-UC PARTNERSHIP

CRC partnered with UC on the Ricelands Salmon Project in 2018 after a strategic planning cycle. The commission was already heavily involved with providing waterfowl habitat through timely winter flooding of rice fields. Having heard about the success of the Nigiri project, Buttner said, the board of directors wanted to expand their rice field habitat programs to include salmon.

“They showed very simply that salmon grow very fast in winter-flooded rice fields,” he said. “There’s no other habitat type in the Sacramento Valley that we’re aware of where they can grow as fast as in flooded rice fields. They’re literally swimming through their food, which is at very high densities. They just eat these bugs aggressively while in the rice fields.”

The Ricelands Salmon Project research targets natural-origin or wild salmon that volitionally – on their own – visit floodplains when the Sacramento River spills over weirs. This is known as the wet side of the levee. Of particular interest is state and federally listed spring-run and winter-run Chinook salmon.

The complementary Fish Food Program, conducted by CalTrout in partnership with CRC, involves winter-flooding of rice fields frequently on the dry sides of levees. After at least three weeks to allow the zooplankton to grow in the fields, growers drain the food-rich water into the Sacramento River.

The project is designed to augment the food supply during the December-April salmon out-migration. It is currently funded by California Natural Resources Agency and Bureau of Reclamation grants administered by Reclamation District 108. During the 2024-25 winter, more than 59,000 rice acres were flooded multiple times for fish food production, according to CalTrout figures.

PROOF OF CONCEPT

The Ricelands Salmon Project research was conducted in two phases, with the first three years – 2018-2021 – essentially a proof of concept, Rypel said.

Using small half-acre plots at River Garden Farms, they examined the best ways to manage post-harvest rice fields with fish survival in mind. The treatments included putting canals and/or ditches through the plots, dumping old Christmas trees, or disking and stomping leftover straw.

There was no statistical difference among the treatments, which Rypel said was a bit surprising. To keep things simple and provide grower flexibility, the researchers decided to recommend disking and stomping rice straw after harvest. Although many rice producers use the practice to manage post-harvest straw, he said it isn’t commonly done in the bypasses.

The researchers also examined optimum flood depth. They found 10 to 12 inches of water helped minimize salmon predation by wading birds. By comparison, rice producers strive for a 3- to 4-inch flood during the growing season.

When fish in the plots reached an average migratory size of about 70 millimeters – about 2.75 inches – the researchers implanted acoustic tags and released them into the Sacramento River to track survival downstream to the Golden Gate Bridge. They had to wait at least another month until fish in the river reached the same size and were large enough to implant the tags.

The plot-raised fish had twice the survival of the river-raised ones, although Rypel said it was difficult to untangle the reason.

“You want as big of salmon as you can and you want them as early as you can,” he said. “That’s what you get with the rice field strategy, so it appears there’s a real benefit to being big and early.”

EXPANDING TO A COMMERCIAL FIELD

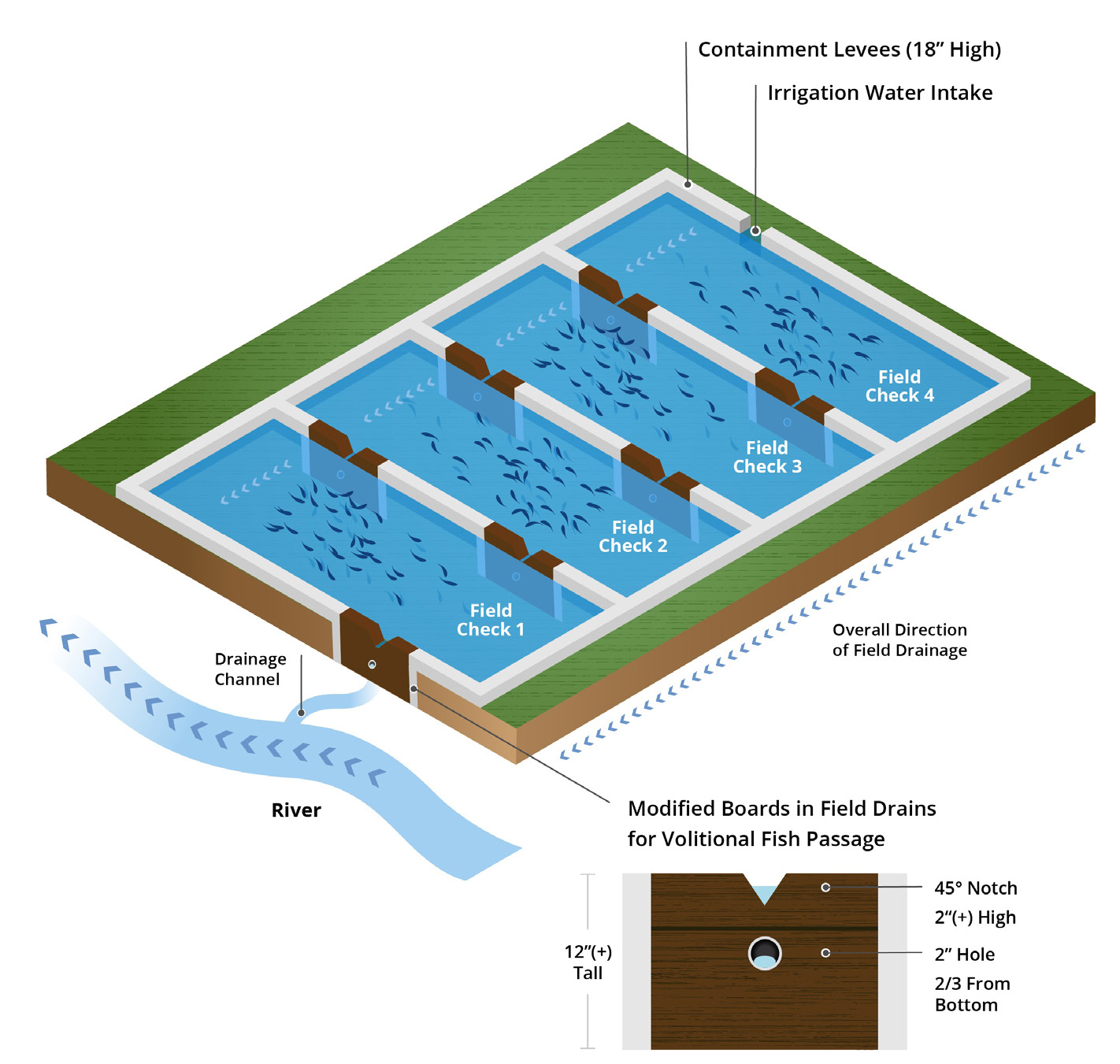

During the second phase from 2021-24, researchers expanded their work to the Sutter Bypass and a commercial-sized 125-acre rice field divided into five checks or paddies. The researchers had designed specialized wooden boards that could be installed in concrete rice boxes leading into and within the field to hold water once flooding began to recede. Atop the stack of boards was one with a 2-inch deep V-notch that allowed water to flow into the field or between checks. About 8 inches from the bottom of the stack was a board with a 2-inch hole that provided fish free access out or within the field.

One question posed by the fishery agencies was whether the fish could easily swim through the boxes from the top of the field to the bottom and out to the river. Using 4,500 tagged hatchery fish, the researchers tracked fish movement and found they were not encumbered.

Ideally, the river would top the weirs shortly after New Years and spread out on the flood plain, including the rice fields. With boards in place, the fields would remain flooded until March 1 even if the river receded beforehand.

The researchers settled on the March date to evacuate resident fish from the field because previous studies showed the earliness helped maximum out-migration survival, Rypel said.

During the 2021-22 drought year, the Sutter Bypass never flooded properly and the field didn’t experience an influx of wild-origin salmon. Instead, the researchers used hatchery-raised fish. The 2022-23 winter provided near-ideal conditions with flooding in early January. Wild-origin fish soon followed.

To determine species using the flooded rice field as well as residency time, the researchers placed a fyke net at the field drain to catch everything exiting. This net was checked daily in accordance with the project’s operating permits.

They found 17 unique species with the bulk being Chinook salmon. Other minor species included Sacramento splittail minnow, threadfin shad, sunfish, steelhead trout, golden shiner and goldfish. Predators included largemouth bass, Sacramento pikeminnow and black bullhead.

Previous work had found the bulk of the Chinook using the rice field were fall-run, followed by fall-spring hybrids, spring-run and to a much lesser extent, winter-run and fall-winter hybrids.

LOW SALMON NUMBERS PROMPT PIVOT

The Coleman National Fish Hatchery, located near Redding, is the primary source of hatchery-raised fall-run Chinook salmon for the Upper Sacramento River. Extremely low numbers of salmon returning to the hatchery to spawn in 2024 followed a similar scenario in 2023. The overall poor outlook for the fall-run prompted the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to close the commercial ocean salmon fishing season for two consecutive years, 2023 and 2024, and likely for a third this year.

State and federal fishery agencies also did not renew the researchers’ necessary permits for the 2024-25 winter since their work involved threatened and endangered Chinook species. But that didn’t stop the research, Rypel said. They continued in small plots to double check a few questions that remained.

Among those was the predation rate within flooded rice fields. Using hatchery-raised salmon and predatory fish species, they examined mortality levels as they related to predator numbers.

During the cold winter months, the predatory bass were sluggish and weren’t a major threat to the resident juvenile salmon, Rypel said. As the water warmed, the bass became more active. The results reinforced the March 1 deadline to evacuate the fish from the floodplain before the predators became too aggressive.

Because they weren’t able to conduct full-field research in 2024-25, Buttner said he may seek a one-year extension on their NRCS grant.

Buttner said an alternative would be for CRC to apply for continuing funding under the NRCS Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) with a possible cap on the number of acres to be enrolled. This would provide additional time to further adaptive management during the first few years of the practice’s initial implementation. Under RCPP, NRCS works with partners, ag producers and private landowners to address local and regional natural resource concerns. Participants are eligible for cost-share.

Buttner is still developing a cost-share proposal but said it will likely be attractive to rice producers. Only about 30,000 acres of Sacramento Valley rice fields are located within the floodplain, and the goal is to have as many landowners as possible enroll in it.

“Only 6% of California rice acreage has the ability to enhance survival of natural-origin salmon — that’s pretty powerful,” he said. “It speaks to why we have such an intense interest to get things going to help these natural-origin fish.”